31

WHAT'S INSIDE COVER STORY

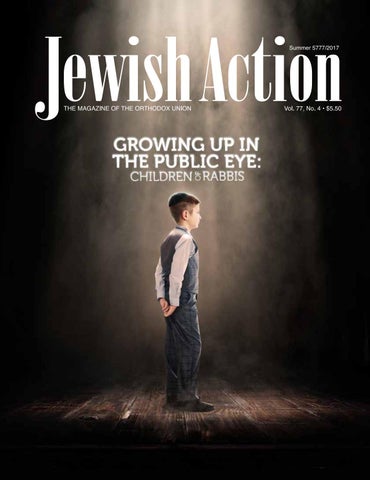

Growing Up in the Public Eye

Cover: Andrés Moncayo

FEATURES

14 22

26

HISTORY A Business of Her Own By Faigy Grunfeld PROFILE Q & A: Up Close with Children’s Author Bracha Goetz By Avigayil Perry What’s on Your Child’s Reading List This Summer?

DEPARTMENTS

2

4

8

12

64 73

84

46

14

LETTERS PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE The Time Is Ripe for a National Conversation By Mark (Moishe) Bane FROM THE DESK OF ALLEN I. FAGIN Some Personal Reflections on Communal Discourse CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE By Gerald M. Schreck INSIDE THE OU INSIDE PHILANTHROPY

32 38

COVER STORY Growing Up in the Public Eye: Children of Rabbis In the Limelight By Bayla Sheva Brenner Rabbi's Son Syndrome By Dovid Bashevkin

46

50

RABBINICS Majoring in Rabbinics By Barbara Bensoussan EDUCATION The Battle for Safe Schools By Nechama Carmel

Rn

80

KOSHERKOPY What Could Be Wrong With . . . ? By Eli Gersten

84

WELLNESS REPORT Stress Less This Summer By Shira Isenberg

88

THE CHEF’S TABLE Simply Elegant Summertime Meals By Norene Gilletz

92

BOOKS Making It Work: A Practical Guide to Halacha in the Workplace By Ari Wasserman Reviewed by Yosef Gavriel Bechhofer

96 98 100

104

Nehemiah: Statesman and Sage By Dov S. Zakheim Reviewed by Daniel Renna Reviews in Brief By Gil Student LEGAL-EASE What’s the Truth about . . . the Apple in the Garden of Eden? By Ari Z. Zivotofsky LASTING IMPRESSIONS The Making of a Jewish Wedding By Kylie Ora Lobell

Jewish Action seeks to provide a forum for a diversity of legitimate opinions within the spectrum of Orthodox Judaism. Therefore, opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the policy or opinion of the Orthodox Union. Jewish Action is published by the Orthodox Union • 11 Broadway, New York, NY 10004 212.563.4000. Printed Quarterly—Winter, Spring, Summer, Fall, plus Special Passover issue. ISSN No. 0447-7049. Subscription: $16.00 per year; Canadian, $20.00; Overseas, $60.00. Periodical's postage paid at New York, NY, and additional offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Jewish Action, 11 Broadway, New York, NY 10004.

Summer 5777/2017 JEWISH ACTION

1

LETTERS

HOW A MINHAG EVOLVED I have followed with interest the discussion concerning standing for a chatan and kallah as they walk down the aisle (“What’s the Truth about Standing for a Chatan and Kallah?,” by Ari Zivotofsky [winter 2016]). This now-universal practice was virtually unheard of until the late 1980s. It is difficult to imagine that from the 1940s until the 1980s, when thousands of weddings were presided over by rabbanim and roshei yeshivah of a generation ago, the then-universal practice of remaining seated was halachically problematic. In fact, I have read that Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, Rabbi Yaakov Kamenetzky and Rabbi Yitzchak Hutner, zichronam livrachah, all did not stand during the chuppah procession. I would ask the following of Jewish Action readers: If you were married before 1990, take out your wedding album. Most likely, you will not see anyone standing while you and your spouse walked down the aisle. This is a fascinating demonstration of how minhagim evolve. Peretz Perl Brooklyn, New York

THE MAGAZINE OF THE ORTHODOX UNION www.ou.org/jewish_action

Editor in Chief

Nechama Carmel carmeln@ou.org

Assistant Editor

Sara Olson

Literary Editor Emeritus

Matis Greenblatt Book Editor

Rabbi Gil Student Contributing Editors

Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein • Dr. Judith Bleich Rabbi Emanuel Feldman • Rabbi Hillel Goldberg Rabbi Sol Roth • Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter Rabbi Berel Wein Editorial Committee

Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin • Rabbi Binyamin Ehrenkranz Rabbi Avrohom Gordimer • David Olivestone Gerald M. Schreck • Rabbi Gil Student Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb Director, Design & Branding Carrie Beylus Design Andres Moncayo; Deena Landau

THE EFFECTS OF DIVORCE Thank you for your excellent coverage of a topic that needs to be addressed—divorce and its effects on children (spring 2017). I especially appreciated Avigail Rosenberg’s “Children After Divorce,” which was practical and encouraging. “The Data on Divorce” interview with clinical psychologist Dr. Yitzchak Schechter was helpful as well—hard facts are indisputable. However, statistics do not reflect the whole story. For example, in the study cited, when questioned, many divorced people said that they were doing well. How was that measured? Are their children not suffering from the breakup of their homes? Thanks again for your wonderful magazine. Malka Kaganoff Jerusalem, Israel

Advertising Sales

Joseph Jacobs Advertising • 201.591.1713 arosenfeld@josephjacobs.org

Subscriptions 212.613.8137

ORTHODOX UNION President

Mark (Moishe) Bane Chairman of the Board

Howard Tzvi Friedman Vice Chairman of the Board

Mordecai D. Katz

Chairman, Board of Governors

Henry I. Rothman

Vice Chairman, Board of Governors

Gerald M. Schreck

Executive Vice President/Chief Professional Officer

Allen I. Fagin

Chief Institutional Advancement Officer

Parental alienation is a significant problem in the Orthodox community that should have been addressed in your articles on divorce. Unfortunately, the topic is rarely acknowledged by the community or by community leaders. Too many parents suffer silently each day, hoping that someday their children will realize that there is another side to the story, and that the alienated parent still loves and cares for them, despite what they may have been told. I am hopeful that one day I will reconnect with my children. Anonymous DR. YITZCHAK SCHECHTER RESPONDS I thank the letter writers for their important comments. It is gratifying to see that the article is generating much discussion. Parental alienation and the effects of divorce on children are two very important aspects that require further analysis and study. As I mentioned in the interview, we have only begun to release the findings of our study of divorce in the Orthodox community. Data is essential to turn insight into action. As important as data is, however, it is not the be all and end all of decision-making nor the sum 2

JEWISH ACTION Summer 5777/2017

Arnold Gerson

Senior Managing Director

Rabbi Steven Weil

Executive Vice President, Emeritus

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Chief Financial Officer/Chief Administrative Officer

Shlomo Schwartz

Chief Human Resources Officer

Rabbi Lenny Bessler

Chief Information Officer

Samuel Davidovics

Chief Innovation Officer

Rabbi Dave Felsenthal Director of Marketing and Communications

Gary Magder

Jewish Action Committee

Gerald M. Schreck, Chairman Joel M. Schreiber, Chairman Emeritus © Copyright 2017 by the Orthodox Union. Eleven Broadway, New York, NY 10004. Telephone 212.563.4000 • www.ou.org.

Twitter: @Jewish_Action Facebook: JewishAction

total of people’s experiences. There are many other pieces to consider with regard to divorce, and we do not pretend that our current understanding is comprehensive. There is much work for us and others to do, and I look forward to keeping Jewish Action readers updated as further findings emerge. IVF, GENDER SELECTION AND HALACHAH In “The Future of Reproductive Medicine: What Does Halachah Say?” (spring 2017), the authors write: “Regarding sex selection using IVF, only when there are medical reasons to engage in IVF can sex selection be considered as a halachic option.” Rabbi Dr. Avraham Steinberg, author of the Encyclopedia Hilchatit Refuit (Encyclopedia of Jewish Medical Ethics), recently wrote the following in an e-mail to me: “I spoke with Rabbi Asher Weiss and Rabbi Zalman Nechemia Goldberg and both clearly stated that there is no halachic prohibition to [engage in] IVF-PGD in order to have the other gender in [the] case of [a family] with four or five children [of the same gender]. Rabbi Weiss added that he does not encourage a couple to do so, but if asked—and there is a strong [desire from the parents] to have the other gender—he allows it.” Richard V. Grazi, MD Genesis Fertility and Reproductive Medicine Brooklyn, New York

MEMORIES OF THE SIX-DAY WAR I very much appreciated your section on the Six-Day War (“Jerusalem Reunited: 50 Years” [spring 2017]). In my mind, Yom Yerushalayim is tied to a different time and place. Fifty years ago, my husband, Rabbi Saul Koss, was an American army chaplain and we were stationed in Germany. Several times a year, a retreat would be held for Jewish personnel and their families stationed throughout Europe; these were held at Hitler’s famous mountain retreat center in Berchtesgaden, Germany, which had been taken over by the US military. On the evening of June 7, 1967, in the midst of one such retreat, a number of us were sitting in a local café, discussing the escalating war in Israel when the conductor of an Austrian band that had been playing came over to our table (the kippot revealed our identity). He cried: “Jerusalem is in your hands!” Suddenly, the band suddenly began playing Hava Nagilah and we, full of emotion, celebrated this extraordinary victory, while stamping our feet on the ashes of Hitler. Here we were in the heartland of Nazism and we were not only still around, but we had won! Susan Koss Silver Spring, Maryland We want to hear from you! Send letters to the editor to JA@OU.ORG

JEWISH EDUCATION HAS ALWAYS BEEN YOUR PRIORITY.

WHY STOP NOW?

Summer 5777/2017 JEWISH ACTION

3

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE

THE TIME IS RIPE FOR A

NATIONAL CONVERSATION By Mark (Moishe) Bane

I

t is time for American Orthodox leaders to begin a national discussion regarding communal priorities and resource allocation. Our community has evolved from the fledgling start-up of earlier days into a robust, growing and increasingly complex society. Marvin Schick, in his Avi Chai day school surveys, reports that Orthodox day school enrollment has increased by more than 38 percent in the past fifteen years, and the number of Orthodox Jewish children enrolled in special needs programs has increased by 204 percent in the same period. The pages of this magazine have reported on the rising divorce rate within the Orthodox community, as well as the increasing prevalence of both alcohol and drug abuse. Homes for battered Orthodox women have been established, and organizations for LGBT individuals seeking to remain within the Orthodox community have sprung up, often to much controversy.

4

JEWISH ACTION Summer 5777/2017

These developments, some terrifying and others wonderful, introduce new responsibilities. One of these responsibilities is the duty of leadership, on a national level, to review the numerous opportunities and challenges facing the community and assess the relative priority, weight and attention that each issue deserves. This type of global review is compelled by the limited resources that are available to address communal needs collectively. Currently, both communal and personal resources tend to be distributed to those who scream the loudest or campaign for support with the most charisma. Often, needs that may be more fundamental to communal survival are neglected in favor of needs that, although legitimate, have a far lesser consequence on a community-wide basis. Moreover, little attention is paid to the duplication of efforts within the community, the respective effectiveness of alternative projects addressing identical or overlapping issues, and the need to assess which communal concerns are more effectively addressed by smaller institutions and which would be handled more efficiently through a larger collective effort. Currently, each cause has its own advocates, and each approach its own adherents. Only an objective analysis, performed by the most trustworthy and respected communal leaders, can reliably identify redundancy and duplication, and prioritize the allocation of resources based upon an assessment

of the impact that each issue may have on the growth of the community— both physically and religiously. This assessment, which may well include different views, should be distributed, and thereby serve to guide the allocation of the community’s valuable resources, whether financial, intellectual or human capital. No single body or institution can undertake such an endeavor alone. We at the Orthodox Union are certainly proud of our programs, initiatives and accomplishments. Other very effective Orthodox communal institutions continue to make invaluable contributions. Individually, however, each organization has its own focus and responsibilities, as dictated by its institutional history, its primary constituency of supporters and its leadership. At the OU, we continually reassess our priorities after monitoring our programs’ impact and effectiveness, and after considering ever-evolving communal needs. I assume that other organizations do the same. But these assessments address only allocations made internally, within a single institution. There is no forum for conducting an objective assessment on a national, community-wide basis. Moreover, guidance on communal resource allocation, for the most part, Mark (Moishe) Bane is president of the OU and a senior partner and chairman of the Business Restructuring Department at the international law firm, Ropes & Gray LLP.

Geography, however, is no longer the dominant factor in identifying segments of the Orthodox community. The remarkable advances in technology, transportation and communication allow individuals and families of like mind or culture to collectively identify themselves as a “local community,” even when they reside great distances from one another.

is provided by individuals already invested in a particular aspect of communal needs, usually areas that happen to be the focus of an institution or project they either founded, support or work for. Such views fail to carry the requisite credibility to sway communal priorities, even when the individuals providing advice are highly regarded and have unassailable reputations. As described below, American Orthodox leadership lacks authority, and thus its views have sway only to the degree determined by the community. While Orthodox leaders frequently have a particular group of followers who adhere to their guidance, on a communal-wide basis little deference is paid to their opinions. Alas, such deference must be earned. I suggest that were communal leaders to expend their valuable time on the interests and needs of the broader Torah community, even sacrificing a degree of focus on their own institutions and respective personal day-to-

day responsibilities, they would thereby exhibit love and respect for other Orthodox leaders and sub-communities across cultural and sociological divides. Moreover, they would then engender the respect and deference that would ensure that their guidance will be acknowledged and followed. To fully appreciate the necessary components of a broad-based communal needs assessment, and to understand why our communal leaders should make this a priority, we must first recognize the nature of contemporary Orthodox leadership and its limited power, and understand why our community currently has no leadership that is actually national in form. The Nature of Contemporary Orthodox Leadership American Orthodox leadership lacks authority, and thus exercises influence only through social pressure. Admittedly, social persuasion is powerful, partic-

“ We knew YU was the place our

children could accomplish everything they wanted in a fully Jewish environment.

“

“Having attended YU and benefited from its education and religious culture we felt confident that it would provide those same opportunities for our children. With its balance of Limudei Kodesh and challenging academics, we knew YU would provide our children with the preparation needed for their careers as professionals, as well as reinforce the religious ideals that they will take with them in all that they do. The same values that permeated the walls of YU when we attended 35 years ago are the very values that we chose to inculcate in our children. Today, our daughter is a sophomore at Yeshiva University. We are thrilled with the education she is receiving and her growth in Torah. She couldn’t be happier.” Michele & Jody Bardash YU Parents

www.yu.edu | 646.592.4440 | yuadmit@yu.edu

LEARN MORE! yu.edu/enroll

Summer 5777/2017 JEWISH ACTION

5

ularly as imposed through community schools’ admission policies and, even more so, through the shidduch process. Nevertheless, individuals and families are subject to these pressures only by dint of voluntarily seeking to integrate into the community. Unlike in past eras and in other lands, American religious communal leadership is neither government mandated nor government appointed. No Jew is compelled to associate with the Jewish community, and those who do may freely decide whether or not to associate with the Orthodox community. Similarly, even Orthodox Jews wholly committed to observance are not required to belong to a congregation, and no congregation is forced to belong to an association of congregations. Unlike many other organized American religious communities, each Orthodox congregation has full autonomy to select its rabbinic and lay leadership, and individual rabbis and lay leadership groups are free to establish their own internal policies and practices. By the same token, of course, community members, rabbis and congregations are entitled to react as they wish, and express their views regarding the Torah authenticity and validity of the policies adopted by others. Not only are our leaders handicapped by the absence of enforcement authority, and the array of social options available to communal members, but they are further weakened by the prevailing culture that idealizes autonomy, and imposes a zealous focus on individuality and an Ayn Rand-like derogation of respect for collective identity and responsibility. Since American Orthodox leadership lacks enforcement authority, it can only exert influence by engendering the respect of communal members or by providing the inspiration necessary to earn the deference of the community. Our leaders’ participation in a national conversation regarding communal priorities will not only produce invaluable thoughts and insights, it will also significantly elevate our leadership’s status and its ability to influence the broader community. Among other discussions, 6

JEWISH ACTION Summer 5777/2017

they would evaluate the relative impact and priority of various communal concerns and opportunities. They would consider the effectiveness of competing approaches to addressing a communal need, and identify efforts that might be revamped or consolidated. By acting and working collectively, a true national leadership will emerge, accompanied by the respect and deference due to authentic national leadership. What Is a “National” Organization? Our community is currently sorely lacking in national leadership—at least as such term must be properly understood. It is thus no wonder that so many

The rich array of cultures and paths within Orthodoxy preserves the majesty of our history and the centrality of our mesorah. The vibrancy of multiple styles and approaches allows families and individuals to express their allegiance to Torah in a manner aligned with their needs. of us have a cynical view of leadership, and few individuals occupying high-level positions of communal responsibility enjoy broad-based respect. National leadership, however, can be reinvigorated, and its fruit would be sweet and plentiful. The American Orthodox community is a conglomeration of communal segments of varying sizes. In earlier times, the parameters of each segment were based on where its members lived. Community organizations were categorized by their respective geographic breadth, reflected by the geographic expanse of where their participants lived, and the geographic reach of their respective influence. An institution servicing a local neighborhood was distinct from one that addressed the needs of an entire city, and even more

so as compared to one that engaged a full region. An organization focusing on the interests of Jews living across the United States was regarded as a national organization. Geography, however, is no longer the dominant factor in identifying segments of the Orthodox community. The remarkable advances in technology, transportation and communication allow individuals and families of like mind or culture to collectively identify themselves as a “local community,” even when they reside great distances from one another. Thus, while American Orthodoxy remains an amalgamation of smaller community segments, each sub-community is now primarily recognized by its members’ cultural and sociological allegiances and identity, and not necessarily by the neighborhood in which they reside. This is even true of Chassidic courts, origin-based sub-communities, and sub-divisions of the Orthodox world distinguished by ideology or lifestyle. Similar to the redefinition of Orthodox sub-segments, an organization is now “national” only if its influence and constituency encompass a broad range of distinct sub-communities. A truly national organization is one with which all observant American Jews affiliate. While several prominent organizations enjoy impressive geographic scope, from a cultural and ideological perspective, each actually functions as a “local” organization, to one degree or another. Even the OU, with its increasing breadth of influence and involvement, is by no means national. The segmentation of American Orthodoxy is healthy and inevitable. The rich array of cultures and paths within Orthodoxy preserves the majesty of our history and the centrality of our mesorah. The vibrancy of multiple styles and approaches allows families and individuals to express their allegiance to Torah in a manner aligned with their needs. In addition, particularly for young people, the intense identification enjoyed with one’s social sub-segment strengthens social loyalty, which serves as an effective barrier to the abandonment of Torah Judaism, and a frustration of assimilation in

general. There are few more impactful tools in engendering commitment and loyalty than identification with cohorts of similar goals and ideologies. While all of Torah Jewry surely shares a uniform aspiration of serving Hashem as directed by the Torah, a more specific identification with a particular approach merely strenghtens one’s sense of identity and affiliation. Each sub-community typically has ideological, cultural or socio-economic distinctions that require tailored approaches in many areas, most prominently in the fields of education and social services. The unique characteristics of communal sub-segments should not, however, eliminate or negate kehillah-wide responsibilities. Contending with the impact of technology and other cultural threats to the Torah belief system of the younger generation, addressing social and health concerns unique to an observant Jew, and dealing with tuition affordability

Not only are our leaders handicapped by the absence of enforcement authority, and the array of social options available to communal members, but they are further weakened by the prevailing culture that idealizes autonomy, and imposes a zealous focus on individuality and an Ayn Rand-like derogation of respect for collective identity and responsibility.

are examples of important communal concerns that transcend segmentation. Unfortunately, the paucity of collective thinking and cross-segment discussion compromises the likelihood that these very serious concerns will be solved any time soon. Finally, I believe that participation in community-wide discussions will evidence selflessness, objectivity and mutual respect. By coming together to engage in a national conversation, American Orthodox leadership will raise its stature in the eyes of American Orthodox Jewry. Perhaps most significantly, by working collectively and addressing challenges and opportunities that transcend one’s own particular community, Orthodox communal leaders will collectively constitute an authentic national leadership. Thereby, American Orthodoxy will be blessed with the national leadership that it sorely needs, and our leaders will receive the deference and influence they truly deserve.

NOWHERE BUT HERE Yeshiva University’s commitment to ensuring that all students can enjoy an uplifting Torah education and a fulfilling college experience includes distributing $42 million in scholarships and financial assistance, benefiting 80% of students. Unlike most universities, YU’s financial aid office considers parents’ obligations to pay yeshiva tuition for siblings. Achieving their academic and spiritual goals is why YU students meet with outstanding success. Applying to graduate programs and entering their chosen careers, 94% (44 students) were admitted to medical school, 96% (27 students) to dental school and 100% (60 students) to law school in the past year.

REACH OUT TO US YUADMIT@YU.EDU | 646.592.4440

Summer 5777/2017 JEWISH ACTION

7

FROM THE DESK OF ALLEN I. FAGIN

SOME PERSONAL REFLECTIONS ON COMMUNAL DISCOURSE

T

his past February, the OU distributed to its member shuls the responses of its Rabbinic Panel to questions posed to it regarding women’s ordination and related issues, together with a Statement from the OU regarding these responses. To summarize their primary conclusions, the Panel determined that women: (i) should not be appointed to serve in a clergy position (i.e., carrying out the duties generally expected from, and often reserved for, a synagogue rabbi); and (ii) could, with the guidance and approval of the synagogue’s lay and rabbinic leadership, carry out a wide array of critical roles, including teaching classes and shiurim; serving as a scholar-in-residence or community educator; serving as a professional counselor to address the spiritual, psychological or social needs of the

8

JEWISH ACTION Summer 5777/2017

community; serving as a mentor to guide women through the conversion process; serving in senior managerial and administrative positions within the synagogue; and (with the approval of the synagogue’s or community’s rabbis, and in close consultation with them) serving as a yoetzet halachah. Reactions to the responses and the accompanying OU Statement were virtually instantaneous; they were numerous, varied and often vociferous. Many of the reactions—from communities across the country—hailed the documents as a significant step forward in expanding the opportunities for women to serve Orthodox congregations and communities in multiple, significant— and halachically acceptable—ways. Other reactions—perhaps predictably— were quite negative, questioning both the substance of the Rabbinic Panel’s Responses, the necessity for having solicited them and their potential impact on the unity of our community. I have no intention in this forum of either reprising these arguments—either for or against —or debating their substance or merits. Perhaps on another occasion. What follows, however, are some purely personal reactions to the manner in which the various reactions unfolded and, perhaps in the process, some observations (again, purely personal) on how our community can productively engage in reasoned discourse on matters that are complex, nuanced and often divisive. I want to stress that

these views are my own, and I share them not only because I believe them deeply, but also to encourage rigorous, thoughtful and respectful discussion about them that can hopefully strengthen us as a community. Conversation vs. Sound Bites One of the more distressing reactions to the debate was the all-too-frequent absence of meaningful analysis; the inability to recognize or appreciate subtleties and alternative vantage points; the reduction of complex thoughts and issues to simplistic sound bites. My distinct impression in reading a number of the comments was that the authors had failed to read (or to completely read) the material they were commenting on, relying instead, it often appeared, on misleading headlines or the summaries of others. Perhaps some of this superficiality can be attributed to a desire to argue rather than to reason, to demarcate rather than to converse. F. Scott Fitzgerald defined “the test of a first-rate intelligence” as “the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” I have no doubt that our community is largely populated by those with first-rate intelligence; we need to train ourselves to be more reliant on it. Allen I. Fagin is executive vice president of the OU.

One culprit standing in the way of real communal conversation is the ubiquitous use of social media as the medium of choice for social discourse. For all of its benefits, the digitalization of discussion has, in my view, left us increasingly bereft of the ability to reason together. In her recently published New York Times bestseller Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age, author Sherry Turkle documents the impact of digital communication on our ability (or inability) to converse with one another: Although the web provides incomparable tools to inform ourselves and mobilize for action, when we are faced with a social problem that troubles us, we are tempted to retreat to what I would call the online real. There, we can choose to see only the people with whom we agree. And to share only the ideas we think our followers want to hear. Real conversation requires listening—the recognition that a subject of consequence is more complex than one may have imagined. It requires the openness to changing one’s mind, in whole or in part. Real conversation requires courage and compromise. It involves moving beyond mere sound bites. One can elect to avoid meaningful conversation both on and off the web; the infatuation with the “online real” just makes it a lot easier to do so. The remarkable technology that makes it possible to interact with everyone does not necessarily result in everyone interacting. Quite the contrary. As Turkle concludes: The web promises to make our world bigger. But as it works now, it also narrows our exposure to ideas. We can end up in a bubble in which we hear only the ideas we already know. Or already like. The Philosopher Allan Bloom has suggested the cost: “Freedom of the mind requires not only, or not even especially, the absence of legal constraints but the presence of alternative thoughts. The most successful tyranny is not the one that uses force to assure uniformity, but the one that removes awareness of other possibilities.”

The Hierarchy of Pesak I do not believe that anyone can seriously doubt that the Rabbinic Panel we approached was comprised of seven of the most distinguished halachic decisors of our community— individuals of unparalleled reputation and integrity, to

Halachah is not determined by popular petition, or op-eds or Facebook posts.

whom broad segments of our community have routinely turned for pesak on matters of personal and communal import and consequence. Yes, there were those within our community who disagreed with their pesak. But such disagreement must acknowledge a fundamental principle that is foundational to our lives as Orthodox Jews—pesak is not democratic; it is, by its very nature, hierarchical. Not every rabbi is a posek (certainly not in the sense of determining halachah in matters of true novelty, or those that affect broad issues of significant communal concern). In such instances we turn to gedolim. If I needed medical advice for a family member with a critical health issue, I wouldn’t turn to my general practitioner. I would seek the opinion of the foremost medical authority I could find. The realm of halachic determination is not, and should not, be different. In short, halachah is not determined by popular petition, or op-eds or Facebook posts. It is the province of controlling halachic texts, as elucidated by our mesorah and the careful, systematic explication of the Torah and Torah values by renowned halachic authorities using time-honored methods of halachic analysis developed and accepted over the millennia. As committed Jews, we accept the authority of our gedolim, who in each generation translate Hashem’s will into practical halachic determinations for the Torah community.

Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, zt”l, decried the populist approach to halachic determination. The determination of halachah is not a democratic act, in which every intelligent person may engage. To the contrary, Rav Soloveitchik argued, “when people talk of a meaningful Halacha, or of unfreezing the Halacha, or of an empirical Halacha,” they are basically proposing an egalitarian approach to the determination of normative halachic conduct—an approach that may align with our democratic sensibilities, but which flies in the face of the halachic system that has guided and sustained us for 2,000 years. Civility Matters The line between zealous advocacy for one’s point of view and language that is demeaning, disrespectful—or worse—surely is somewhat porous and occasionally subjective. But much of life requires us to exercise such judgments, and remain on the right side of the line—all the more so when respect for talmidei chachamim is at issue. Fortunately, much of the debate, while intense, remained dignified. I particularly commend the Lehrhaus Symposium, which invited a number of distinguished participants to comment on the Rabbinic Panel’s Responses and the OU Statement. The participants did so—candidly, occasionally critically, but with respect and due regard for the complexity of the issues. Occasionally, however, the debate engendered by the Rabbinic Responses and the OU Statement crossed that del-

Summer 5777/2017 JEWISH ACTION

9

JEWISH GENETIC NEWS BULLETIN

There’s something you should know... GAUCHER DISEASE IS THE MOST COMMON INHERITED JEWISH GENETIC DISEASE.

Gaucher disease type 1 is the most common form of the disease in the United States and Europe, particularly among Jews of Ashkenazi (Eastern European) descent. DO YOU HAVE ANY OF THE FOLLOWING? Bone and joint issues such as: - Multiple fractures - Diagnosed osteoporosis - Diagnosed osteoarthritis Chronic fatigue Enlarged abdomen Bleeding issues such as: - Easy or frequent bruising

icate line. For example, one writer likened the Rabbinic Responses to a sermon delivered on the eve of the Civil War, defending the institution of slavery. One theme that repeated in a number of blog and other social media posts accused the Rabbinic Panel of formulating their views in order to maintain their “hegemony” as well as their “dominion and control.” Not only was such an argument the height of disrespect,

The Rabbinic Panel . . . emphasized—indeed, repeatedly celebrated—the enormously important and successful roles that women can and must play within our communal and synagogue structures, including as community educators and scholars.

- Frequent nose bleeds - Difficulty clotting after injuries Chronic aches in joints and muscles The good news is that Gaucher disease can be diagnosed with a simple blood test. Proactive treatment can prevent or ameliorate signs and symptoms as well as reduce the risk of irreversible tissue and organ damage. Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) and substrate reduction therapy (SRT) now allow patients to live full and active lives. KNOW THE FACTS! Contrary to what may have been previously shared, the N370S mutation for Gaucher disease is NOT always mild in presentation of the disease. Without proper medical care, those who have even one N370S mutation either undiagnosed or untreated, can have severe future ailments.

5410 Edson Lane Suite 220 Rockville, MD 20852 1200 51st Street PO BOX 190781 Brooklyn, NY 11219

To learn more, visit: gaucherdisease.org/mysymptoms Questions? Call us at: 718-669-4103 10

JEWISH ACTION Summer 5777/2017

it was also entirely illogical. While the Panel made clear that ordaining women as rabbis was at odds with halachah and mesorah, they likewise emphasized—indeed, repeatedly celebrated—the enormously important and successful roles that women can and must play within our communal and synagogue structures, including as community educators and scholars. Regardless of our substantive point of view, can we not all agree that civility in our communal discourse matters? Tone matters. Courtesy and respect for divergent viewpoints, even if they are believed to be fallacious, must be the order of the day. As our sages recognized: “Divrei chachamim be’nachat nishmaim— The words of the wise are most likely to be heard when communicated pleasantly.” Wherever we stand on any issues, particularly those of communal importance, we need to begin with this goal in mind. We have only scratched the surface of the constellation of challenges facing our community. Many of these challenges are not new. The numerous passionate and insightful comments on the Rabbinic Responses and the accompanying OU Statement—from both women and men across the Orthodox spectrum —highlight the need for ongoing, vigorous but respectful discussion. Such a discussion can elucidate the multiplicity of pathways available to meet our communal imperatives while remaining true to halachic and hashkafic norms. Let us pray that our community can truly internalize this imperative, l’hagdil Torah ul’ ha’adirah—to glorify the Torah and ennoble it.

Summer 5777/2017 JEWISH ACTION

11

CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE

By Gerald M. Schreck

A

re books dying? With the advent of digital reading, this question has been explored incessantly online and in print media, as well as in these very pages. Hundreds, if not thousands, of eulogies have been written in anticipation of the demise of printed books, yet it seems that the end of books may not be so near after all. A recent Pew Report found that while a growing number of Americans are reading e-books on digital devices, “print books remain much more popular than books in digital format.” This is heartening news—and yet, while American adults are still reading books, what about kids? According to a 2014 study by Common Sense Media, kids are reading (electronic or print books) less and less for fun as they get older; the study found that 45 percent of seventeen-year-olds say they read by choice only once or twice a year. Reading rates have also declined significantly over the past three decades. According to government studies, in 1984, 8 percent of thirteen-year-olds and 9 percent of seventeen-year-olds said they “never” or “hardly ever” read for pleasure. In 2014, that number rose to 22 percent and 27 percent, respectively. Indeed, why should kids read when they can text, post photos on Snapchat or play an addictive electronic game?

12

JEWISH ACTION Summer 5777/2017

With so many digital distractions out there, it’s surprising that kids are reading at all. I haven’t seen any studies done specifically on the reading rates among Orthodox kids, but I’m fairly optimistic that frum kids are still reading. Firstly, there’s Shabbos, when cell phones are turned off for a blissful twenty-five hours. Secondly, the Jewish children’s book-publishing industry has seen phenomenal growth in recent years. When I was growing up in New York City in the fifties and sixties, there was little Jewish-oriented literature geared for my age. Today, our kids are so very fortunate—there is a plethora of high-quality engaging Jewish children’s books catering to every age and interest. A recent article we published on the exploding Jewish children’s book-publishing industry noted that there are “new publishers, authors and books appearing each year.” The article quoted book shepherd Stuart Schnee, who stated that “more children’s titles are being released by Orthodox publishers than ever before.” Seemingly, frum kids are still reading. And yet, we cannot take anything for granted. In the digital world in which we live, every few months or so, it seems, sees a new digital fad, a new mind-numbing electronic distraction. So even if our kids are still reading books today, there is no guarantee they will still want to read books tomorrow. So what do we do? Whether we are parents, grandparents or great-grandparents, we need to encourage our children or grandchildren to turn off their iPods and iPhones and spend a few minutes enjoying the simple, old-fashioned pleasure of curling up with a good a book. Incidentally, we need to put down our own smartphones and read ourselves. And summer—with its slower pace and longer days—is a perfect time to do just that. With children’s literature a focus in this summer issue, we asked a diverse

group of educators to respond to the following: Which book do you suggest children read this summer, and why? (Warning: while the recommendations are mainly “children’s books,” some of them seem so enticing, you may be tempted to read them!) Additionally, this issue features a Q & A with the well-known Jewish children’s author Bracha Goetz, who shares her insights and advice about the writing process and how to foster a life-long love of reading in children. Our cover story, by the talented Bayla Sheva Brenner, examines the challenges and pressures children of rabbis or other communal figures face while growing up in the public eye. At the same time, it sheds light on another dimension of their lives: the extraordinary spiritual benefits of having parents who are deeply devoted to klal work. “Despite the expectations, visibility and sacrifice,” writes Brenner, “these children of rabbis or high-profile rebbetzins saw close-up what it means to take a community under one’s wing, and to dedicate one’s life to uplifting others.” Also in this issue, researcher par excellence Faigy Grunfeld explores how Jewish women over the ages were active in the business world. (According to the author, there weren’t too many Jewish “stay-at-home” moms in the Middle Ages!) Grunfeld demonstrates how some of these women were, in fact, impressive entrepreneurs who played a vital role in the world of business and commerce. Aside from these thought-provoking articles, this issue offers our usual array of articles on halachah, kashrut, health, recipes and the latest Jewish books. Don’t forget to e-mail your thoughts and comments to ja@ou.org, and best wishes for a healthy and a happy summer.

Gerald M. Schreck is chairman of the Jewish Action Committee and vice chairman of the OU Board of Governors.

APPLY NOW

FOR FALL SEMESTER tcla.touro.edu

Experience the Touro Difference at

Touro College Los Angeles

What if there were a school where you could be nurtured to reach your professional ambitions while upholding your Jewish values? There is! At Touro College Los Angeles, we offer a supportive environment, small personalized classes, and quality educational programs that help you learn the skills and gain the experience you need to succeed. Visit tcla.touro.edu to learn more about our undergraduate programs.

←

Enroll now in our Business, Health Sciences, Judaic Studies, and Psychology programs. Financial aid available for qualified applicants.

Where Knowledge and Values Meet TCLA is a division of Touro University Worldwide

←

TOURO COLLEGE LOS ANGELES

tourola.admissions@touro.edu

Touro College Los Angeles Contact Director of Admissions: Summer 5777/2017 JEWISH ACTION 13 Leah Rosen 323.822.9700

Postcard depicting a Jewish woman, a buyer of secondhand clothing. From the Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York

14

JEWISH ACTION Summer 5777/2017

HISTORY

A BUSINESS OF HER OWN JEWISH WOMEN ENTREPRENEURS OF THE PAST By Faigy Grunfeld

C

lose your eyes and envision the quintessential Jewish woman of centuries past. Perhaps she is stirring a pot that hangs over a fire while singing a Yiddish folksong to her young daughters. Maybe she is rolling pastry dough while urging her boys to get to cheder. Or perhaps she is haggling with vendors at the marketplace, triumphantly brandishing her purchases after securing a sound price. But while the quintessential Jewish woman of the past most likely did stir pots, roll pastry dough and haggle with vendors, she was also a formidable force in the business world. Medieval Professions In Talmudic times, women contributed to their household incomes mostly through spinning and weaving, which were important ancient industries; some sought out extra income by serving as a “wailing woman” at funerals. However, the medieval Jewish woman was a truly impressive commercialist.

Christianity condemned usury because of the Biblical prohibition: “Thou shalt not lend upon interest to thy brother” (Deuteronomy 23:20); however, as Jews and Christians were not considered “brothers,” many Jews took on the role of moneylenders. Because of their connections to Jewish communities around the globe, they were able to access significant funds, and often became indispensable to many princes and nobles. French women like Minna of Worms (eleventh century) and Pulcellina of Blois (twelfth century) were savvy moneylenders and extended services to the nobility in their regions.1 In thirteenth-century England, Licoricia of Winchester dominated the profession, with her name appearing in many business documents along with those of nobles and monasteries. However, the majority of Jewish women who were moneylenders conducted small-scale transactions with their local Christian neighbors. Women were also successful

traders, reflected in travel documents and business inventories. While the most common profession for women was textile production—weaving and embroidery—women were also land-renters and conducted largescale business transactions, and often appeared in beit din, as evident from various documents.2 Farming was another popular profession—at least until the Middle Ages. Jews had been involved in agriculture from Talmudic times until twelfth and thirteenth-century medieval Europe, when they were barred from owning land. One letter, preserved in the She’eilot u’Teshuvot of the Maharam, a medieval Tosafist, highlights the hardships of a particular widow who worked as a farmer.

Faigy Grunfeld teaches English and history. She lives in Detroit, Michigan with her family.

Summer 5777/2017 JEWISH ACTION

15

Detailing the travails of the woman, the letter asks that the Jewish community lower communal taxes. She sweats a lot and eats little. Sometimes the fruit is burnt or becomes decayed or injured . . . the sharecroppers take half the profit.

Madame Minna of Worms, Germany (eleventh century) Minna was respected and admired by Jews and Gentiles alike. Her economic achievements as a successful moneylender brought her to the door of many nobles and wealthy members of society. When the First Crusade passed through Worms, the local gentiles begged Minna to convert rather than condemn herself to death. Below is an excerpt from Mainz Anonymous, one of the three medieval chronicles of Jewish suffering during the First Crusade. A distinguished woman, named Mistress Minna, found refuge below the ground in a house outside the city. The people of the city gathered outside her hiding place and called: “Behold, you are a woman of valor. Perceive that God is no longer concerned with saving you for the slain are lying naked in the open streets with no one to bury them. Yield to baptism.” They fell all over themselves entreating her, as they did not wish to slay her, for her fame had traveled far because the notables of her city and the nobles of the land used to frequent her company. But she answered by saying: “Heaven forfend that I should deny God-on-High. Slay me for Him and His Holy Torah, and do not tarry any longer.” There she was slain, she who praised in the gates. From Shlomo Eidelberg, “Mainz Anonymous,” The Jews and the Crusades (Hoboken, 1977). 16

JEWISH ACTION Summer 5777/2017

Sometimes there are reverses, such as too much sun or too much cold, too little rain or too much rain, or hail or several kinds of locusts.3 Jewish men and women were barred from medieval universities, and therefore had no opportunity to earn a doctorate in medicine (medieval universities awarded these rare degrees after over a decade of study). Many therefore learned the art of healing through apprenticeship. In Frankfurt during the 1420s and 1430s, there were seven Jewish female doctors, four of whom were ophthalmologists. One Yehuda ben Asher records his near blindness and subsequent treatment in his ethical will: Then a Jewess, a skilled oculist, appeared on the scene. She treated me for about two months and then died. Had she lived another month, I might have recovered my sight fully. As it was, but for the two months’ attention from her, I might never have been able to see at all.4 City records indicate there were Jewish female doctors practicing in thirteenth-century Paris, as well as in fourteenth-century Aragon, where one particular Jewess, Floreta Ca Noga, even treated the queen of Spain. Was the “working woman” a widespread personality or was she a rare phenomenon? Evidence of a strong female presence in the workforce is found in the Jewish cannon itself. Medieval rabbinic authorities dealt with a plethora of questions related to female finances. Societal shifts during that period led rabbinic authorities to adjust previous restrictions relating to women doing business with gentiles, swearing in court, traveling alone, and compensating for damages and other liability issues. Rabbi Eliezer ben Natan of Mainz (the Raban, twelfth century), took a more permissive stance than his contemporaries regarding female autonomy in business matters, as indicated in his work, Even HaEzer, section 115: In these days women are legal guardians and vendors and dealers and lenders and borrowers, and they pay and withdraw and collect and deposit

money, and if we say they cannot swear or affirm their business negotiations, then you will forsake these women and people will begin to avoid doing business with them. In many communities, certain professions were reserved for the rabbi’s wife so she could contribute to the family’s earnings beyond the small rabbinic stipend. Her jobs included making Havdalah candles, weaving tzitzit, manufacturing parchment used for Torah scrolls, tefillin and mezuzot, and embroidering curtains for the Torah ark. Businesswomen in the Early Modern Era (1500-1750) By the early modern period, women’s businesses were evolving. After a series of expulsions and crusade attacks, Ashkenazic Jewry slowly began to move to Central and Eastern Europe, burrowing roots in Poland and Lithuania. In this environment, women were again critical to the financial infrastructure. Raszka Fishel was a banker, and so indispensable to the Polish court

Print of a Jewish couple in Frankfurt am Main, 1703, dressed in everyday garb, possibly on the way home from the market. From the Leo Baeck Institute, New York

ION T U L O S T BE H A N A H S THE nd wants g in israel a in rn a le r a e y

ollege? fantastic at about c r has had a h te w h t g u u b a d t, r a hat’s gre Your son o ond year. T c e s a r fo e to continu

TOURO COLLEGE

OLUTIO S E H T S E ID V O R P IN ISRAEL

N

to d Yeshivot eminaries an S e d si g n o rks al eir in Israel wo jumpstart th ro College cessary to e u n To s e d e rs u as ge co er Jerusalem-b erican colle SA or transf heduled Am ge in the U sc lle y o tl C n ie ro n u nve d To provide co ns to atten and want. ur child pla they need yo s r e e rs th u e h co W n ca ers. s the Ameri college care TCI provide y, it rs e iv n u other credits to an

TOURO COLLEGE in ISRAEL

טורו קולג׳ ישראל Where Knowledge and Values Meet

FOR MORE INFORMATION Israel: 02.651.0090 • USA: 1.800.950.4824 • tci.touro.edu • israel@touro.edu *Academic courses taught by Touro College in Israel are part of the curriculum of Touro New York and are limited in Israel to students who are not Israeli citizens or permanent residents. Additional courses must be taken in New York to complete the degree. Financial aid may be available to qualifying students.

Summer 5777/2017 JEWISH ACTION 17 Touro is an equal opportunity institution. For Touro’s complete Non-Discrimination Statement, please visit www.touro.edu.

Pulcellina of Blois, France (twelfth century) Pulcellina was a wealthy moneylender with significant political influence. She had close ties with the region’s Count Theobald V of Blois, with whom she had many business dealings. Because of her political power, however, she had many enemies. The local lord resented her influence with the count, and the local Christians were quick to plot against her. In 1171, a Christian servant saw a Jew watering his horse, with an animal hide resting on the horse’s back. The servant imagined the hide was a Christian child who had been murdered by the Jewish horse owner, and quickly hurried to tell his master. The master relished this opportunity to bring down Pulcellina and her people. The following account is taken from the works of Rabbi Ephraim ben Jacob, a twelfth-century Talmudist and author of Sefer Zechirah: The next morning the master rode to the ruler of the city, to the cruel Theobald. He was a ruler that listened to falsehood, for his servants were wicked. When he heard this [the incident with the “slain child”] he became enraged and had all the Jews of Blois seized and thrown into prison. But Dame Pulcellina encouraged them all, for she trusted in the affection of the ruler who up to now had been very attached to her. However, his cruel wife, a Jezebel, swayed him, for she also hated Dame Pulcellina. [Theobald’s wife was Alix, the daughter of King Louis VII of France.] All the Jews had been put into iron chains except Pulcellina, but the servants of the ruler who watched her would not allow her to speak to him at all, for fear she might get him to change his mind. The end of this story is tragic. Pulcellina was unable to speak with the Count, and thirty-one Jewish lives were lost to death by burning. Pulcellina was offered clemency by the Count, but she refused this if her community was not extended the same. She died with the rest in the fire.

were vulnerable to the bitter cold of Eastern European winters. Despite the prohibition against crossdressing, Rabbi Yoel Sirkis (the Bach, seventeenth century), permitted women to wear the warmer men’s coats.8 Most women involved in commerce had to hustle to make a living, acting as hawkers, stand-owners or wholesalers. Occasionally women were highly successful, as was the case for seventeenth-century Gitl Kozuchowski from Poland who, along with her husband, built a flourishing commercial house. Her husband outlined her role in his will: She is to deal in all business that there is according to her desire and will . . . because she is the lady of the house, dominant and ruling over the entire estate and business for all of her days.9 The Widowed Woman Widowed women had no choice but to be financially active. Glückel of Hameln’s memoir outlines some of her business dealings as a widow.

From Jacob Marcus, The Jew in the Medieval World: A Sourcebook, 315-1791 (New York, 1938), 128-129.

that when the Jews of Cracow were expelled in 1495, Raszka was the only one allowed to remain in the city by order of King Jan Olbracht.5 Raszka was a formidable businesswoman. The men in her family were scholars and mystics, while she dealt with the more practical aspects of life. She acted as lady-in-waiting to the Queen Mother, and convinced the king to use her silver to produce coins in royal mint (and she finagled a fabulous rate for her silver). She secured for her son the post of tax collector for the king, and for her son-in-law, the position of chief rabbi of Poland. Through these appointments, the Fishel family came to dominate many avenues of power in Poland.6 Eventually, poverty in Poland caused Jews to shift from being 18

JEWISH ACTION Summer 5777/2017

moneylenders to money borrowers, so that usury was no longer a realistic profession for Polish Jewry. Industrious women became tavernkeepers or inn-keepers. Indeed, the memorable zydowka (Jewess) who ran the karczma (tavern) has a nostalgic grip on our imaginations. Her responsibilities, including serving, feeding and housing travelers and visitors, seemed to suit her maternal nature, for she filled this role more successfully than her husband.7 There were also cheese-makers, goose-herders, washerwomen and the poorest of the lot—market vendors. Testifying to the presence of Jewish women in the workforce, the latter profession gave rise to the halachic question regarding women wearing men’s winter coats. During those long market days, female vendors

Illuminated page from the Rothschild Miscellany of Sefer Mishlei, showing the “Woman of Valor” as the mistress of the house, giving counsel to her husband and sons. The Miscellany is a collection of illuminated texts from Veneto, Northern Italy, circa 1460-80, housed at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. Photo: Bridgeman Images

Loud travelers are beyond your control. Light shouldn’t be. The SHABBULB TM looks and acts like a traditional light bulb – except for its unique lever. Slide the lever, and tiny covers glide over the LED lights that sit within the bulb. Hide and reveal light as needed without affecting electrical currents. Sunlite’s revolutionary product won’t just light up your room; it’ll light up your life.

CERTIFIED BY THE

Order now at shabbulb.com

Summer 5777/2017 JEWISH ACTION

19

I was busied in the merchandise trade, selling every month to the amount of five or six hundred Reichstalers. Besides this, I went twice a year to the Brunswick Fair and each time made my several thousands profit.10 The widow’s finances certainly deteriorated once she entered this new status, evidence that both men

Licoricia of Winchester, England (thirteenth century) Licoricia was a wealthy Jewess from her youth, most likely due to a large inheritance or ketubah gift. She became an active moneylender while a young woman. Her first husband died, and she remarried David of Oxford, another wealthy English Jew. He similarly passed away after a few years of marriage, and because of his tremendous wealth, all of his possessions were seized for tax evaluation by Henry III. Licoricia was placed in custody to ensure she would not escape with any hidden assets. She was finally released, but only after paying a tremendous sum to the king, who used the funds to rebuild Westminster Abbey in the gothic style. (This was not uncommon in Jewish history. Monarchs have often utilized Jewish wealth to fund their own projects.) After this incident, Licoricia continued to loan funds to the nobility of England. She and her Christian maidservant were murdered by robbers when she was in her fifties. From Emily Taitz, Sondra Henry, Cheryl Tallan, JPS Guide to Jewish Women (Philadelphia, 2003), 80-81.

20

JEWISH ACTION Summer 5777/2017

and women were necessary for a household’s financial stability. Shtetl Life (1750-1940) The Eastern European shtetl11 conjurs up an image of an idyllic world marked by milkmen and water-carriers, bustling marketplaces and cozy wooden homes. But the nostalgia for the simplicity of shtetl life overlooks the unrelenting hardships, extreme poverty and overt anti-Semitism that was part and parcel of shtetl life. Against this backdrop, the shtetl wife was electric, alive, in motion. The shtetl mother was up by 3:00 am and went to bed long after her children. Strong, shrewd, capable and always employed with some task, she defined vitality and grit, and was both affectionately and warily referred to as a “Cossack.”12 Many writers reflecting on life in the shtetl recall that they never saw their mothers sleep. Wives of scholars had to assume the responsibilities of daily life, for their husbands had little experience with paying taxes, tending the vegetables or shoveling snow. This reality prompted many women to say knowingly, “As for Olam Haba, let the men say we can’t get there without them. They couldn’t manage this life alone, no doubt we will have to do the job for them there too.”13 Female productivity in the workforce was so vital, in fact, that when researching a shidduch, many parents would look for a girl who spoke Polish, so she could conduct business with the locals. In some shidduch letters between Rabbi Shmuel of Kelm and his nephew, a prospective girl is described as “educated in reading Hebrew, Polish, German . . . and also the Russian alphabet is not unfamiliar to her.”14 Although unmarried girls were usually absorbed with household chores and helping with the younger children, some instances show these young women working towards their own dowry, as in the case of Rabbi Simcha Zissel Ziv of Kelm’s daughter, who simultaneously earned

her dowry and aided her parents with their finances by running a shop.15 Girls without a dowry or financial stability worked as household servants in wealthy Jewish homes, and after a few years saved up enough to finance their own shidduch. By the nineteenth century, shopkeeping became one of the most widespread occupations for women, especially for wives of Torah scholars in nineteenth-century Lithuania. Rabbi Naftali Amsterdam’s wife ran a bakery, Rabbi Meyer Yonah Barentski’s wife was a merchant and the wife of Rabbi Aderet of Ponovezh managed a dry-goods shop. Many heartfelt letters reflect the anguish of rabbinic scholars who often traveled to other towns for study, leaving their wives to shoulder a multitude of responsibilities, including the children, the business and aging parents. In early twentieth-century America, industrial growth and financial success made it so that women were no longer critical to the family’s earnings. Ironically, these economic and societal improvements actually created a stigma against women who did work. (This reality paved the way for the second wave feminism in the 1960s, which fought for financial independence for women.) So while many of our mothers and grandmothers may have been stayat-home-moms, it is very probable that our great- and great-great grandmothers were industrious businesswomen. Over the millennia, the Jewish woman has drawn upon her many talents, skills and resources to confront a myriad of challenges—be they physical, spiritual or financial. When necessary, she valiantly joined the workforce, adding new responsibilities to her tiringly long list, personifying Rashi’s assertion that women can simultaneously “tend the vegetables, spin flax, teach a woman a song for a fee and warm the silkworms.”16 With remarkable inner strength, tenacity and faith, the Jewish woman occupied her various roles of homemaker, mother, wife, daughter, breadwinner, supporter

A Husband’s Eulogy Dolce of Worms, a thirteenth-century pious woman, earned a livelihood for her family so her husband could devote himself solely to Torah study. (This was not commonplace in medieval Europe, a time when men and women were both vital to the workforce. Rabbinic figures often received a stipend from the community, and their wives brought in supplementary income. Wives supporting husbands learning Torah is more of a nineteenth-century Lithuanian phenomenon.) After her death by the hand of the Crusades, her husband, Rabbi Elazar (the Rokeach), wrote the following eulogy describing her many virtues.

A woman of valor who can find? She was the crown of her husband . . . She sought out white wool with which she wove fringes, with the willingness of her hands. She thoughtfully planned her mitzvot, and was praised by all who saw her. She was like the merchant ships, feeding her husband, enabling him to study. The women who saw her paid tribute to her good merchandise. She gave food to her household and bread to the boys. Her palms held the spindle to weave filaments for the holy books. With alacrity she spun sinews for use in tefillin, megillot and Torah scrolls. Fleet as a deer, she cooked for the boys, catering to the needs of the students. She girded her loins with vigor, sewing forty Torah scrolls. She cooked and set the table for all the men who studied Torah. She forged goodness and adorned brides, starting them off on married life. She willingly washed the dead and sewed their shrouds. Her hands mended both the garments of the students and the torn books. From her labor, she distributed funds to those who study Torah . . . Her lamp would not go out at night as she made wicks for shuls and study halls . . . she organized the regular services, morning and evening. All mitzvot she fulfilled enthusiastically and with great piety. She purchased milk and engaged tutors for her children from her earnings. From Rebbetzin Sarah Feldbrand, From Sarah to Sarah: Fascinating Jewish Women Both Famous and Forgotten (Lakewood, New Jersey, 2005)

and caretaker while managing to raise generations of God-fearing and righteous Jewish sons and daughters.

Notes

1. Baumgarten, Elisheva, “Medieval Ashkenaz (1096-1348),” Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia, 1 March 2009, Jewish Women’s Archive, https://jwa.org/ encyclopedia/article/medieval-ashkenaz-1096-1348. 2. Judith R. Baskin, “Jewish Women in the Middle Ages,” Jewish Women in Historical Perspective, Second Edition, ed. Judith R. Baskin (Detroit, 1998), 105-110. 3. Emily Taitz, et al., The JPS Guide to Jewish Women (Philadelphia, 2003), 87. 4. Israel Abrahams, trans., Hebrew Ethical Wills, Second Edition (Philadelphia, 1976), 165-166. 5. Rosman, Moshe, “Poland: Early Modern (1500-1795),” Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia, 1 March 2009, Jewish Women’s Archive, https://jwa.org/ encyclopedia/article/poland-ear ly-modern-1500-1795. 6. Byron L. Sherwin, Sparks Amidst the

Ashes: The Spiritual Legacy of Polish Jewry (New York, 1997), 62-67. 7. Rosman, “Poland: Early Modern (1500-1795).” 8. Bach commentary on the Tur, YD 182. 9. Rosman, “Poland: Early Modern (1500-1795).” 10. The Memoirs of Glückel of Hameln, trans. Marvin Lowenthal (New York, 1960), 179. 11. This article focuses on the classical trajectory of Ashkenazic Jewry; however, there is a rich history of women in Western Europe, the Muslim Empire (Sephardic), Italy, America and Israel, which is beyond the scope of this article. 12. Menachem Brayer, The Jewish Woman in Rabbinic Literature, vol. 2 (Hoboken, 1986), 57. 13. Ibid., 52 14. Immanuel Etkes, “Marriage and Torah Study Among the Lomdim of Lithuania,” The Jewish Family: Metaphor and Memory (New York, 1989), 166. 15. Ibid., 169. 16. Rashi, Ketubot 66a.

Summer 5777/2017 JEWISH ACTION

21

PROFILE

UP CLOSE WITH

BRACHA GOETZ

A Harvard graduate who just came out with her thirty-third book discusses her decades-long career as a writer of Jewish children’s books

By Avigayil Perry

H

ow did you get started as a children’s author? I always loved reading as a child. Even as an adult, I am drawn to children’s books. I like to write about deep subjects in a simple way, to simplify a deep concept and bring it down to a child’s level. I like geting to the crux of an issue. I’m not a person of many words. I don’t like a lot of embellishment. I wrote my first book while watching my children on the playground. I decided to send it to a publisher, but I had no expectations, so I was surprised to receive an acceptance letter not long after.

What are your favorite children’s books? My favorite books are Dr. Seuss, Charlotte’s Web, Stuart Little, The Catcher in the Rye and The Diary of Anne Frank. I also love Winnie the Pooh by A. A. Milne, the Peanuts comics by Charles Schulz and especially the Happiness Is… books by Lisa Swerling and Ralph Lazar. I enjoy works that use words sparingly, and yet manage to be both deep and delightful. 22

JEWISH ACTION Summer 5777/2017

What are key elements that make a children’s book work? Children love seeing pictures of children. They love funny illustrations with vibrant colors. They also love repetition, but take care—a children’s picture book shouldn’t be too didactic. The book Is it Shabbos Yet? by Ellen Emerman is full of repetition and so many wonderful messages—the kinds of preparation involved in making Shabbos, the joy of Shabbos and the bond between the mother and daughter. My What Do You See? series [a word-and-picture book series for toddlers—What Do You See at Home?; What Do You See on Shabbos?, et cetera] subtly contains vital concepts, such as the need to express gratitude and include everyone in games. If the books are enjoyable, children don’t realize that they’re internalizing these messages. Lessons about simchah and giving, for example, are readily absorbed into a child’s neshamah. Avigayil Perry lives in Norfolk, Virginia, with her family and writes for various Jewish publications.

How do you get your ideas? I like to write books that I wish I’d had as a child, as I didn’t grow up frum. Often I read a non-Jewish book and realize we need a Jewish version. This is how the What Do You See series came about. One of my newer books is called Secrets of the Aleph Beis. I am fascinated by the aleph beis. The book describes how the shape of each letter is meaningful. As my introduction states, “At 22, I found 22 new letters that gave my life new meaning.” Sometimes I see a need, and the idea evolves from there. [For example,] I saw a need for frum children to appreciate nature. Remarkable Park opens a child’s eyes to lessons from nature. Other times I’m asked to write certain books. Not long ago, I was asked by Chevrah Lomdei Mishnah to write a book that teaches children how to keep a connection to someone who passed away. I Want to be Famous is about how shining one’s inner spotlight is far more essential in life than yearning to have a spotlight shine on a person externally. How a soul shines is what really matters. The book contains a quote from Rabbi Yisrael Salanter even though it’s published by a nonJewish publishing company. Have you seen the Jewish children’s market change over time? And if so, how? In 1982, I didn’t have a computer; I used a typewriter. I had to wait around for letters to arrive from publishing companies. Today, with e-mail, I receive an answer immediately. I also have more say over the design. Today, there is also greater receptivity to publishing books on difficult topics. It took four years to get Let’s Stay Safe published. [The book includes

Bracha Goetz reading one of her books. Courtesy of the Baltimore Jewish Times

information about providing protection from abuse.] Talking About Private Places [about the dignity and respect with which our bodies are to be treated]

I’m not a person of many of words. I don’t like a lot of embellishment.

took even longer to get published. Hashem’s Candy Store took time as well—the book raises awareness about eating healthfully. Many schools give out soda cans [and other sugary treats] as prizes, which does not promote children’s health. Ba’alei teshuvah are often not okay with just accepting the status quo; we look to improve certain areas within the frum community. Summer 5777/2017 JEWISH ACTION

23

Picture books need to provide a lot of joy. An important aspect of parenting is filling the home with joy. I have heard that writing for children is much harder than it looks. Why is that? [For me,] writing children’s books flows naturally. [Though the editing process may be slower,] getting into a child’s head is not difficult for me. I tend to see the world through a child’s perspective, with a sense of wonder. Picture books need to provide a lot of joy. An important aspect of parenting is filling the home with joy. What I find most meaningful is when my writing affects a child; the effect can last a lifetime. I get e-mails from people around the world telling me how my work affected them. One Friday night, we had a family over for the Shabbos meal. One of our guests, a twenty-one-year-old young man, was shocked to find out that I was the author of The Happiness Box. As a child, he had experienced bullying.

Reproduced from Let’s Stay Safe, with permission from the copyright holders, ArtScroll/Mesorah Publications, LTD

24

JEWISH ACTION Summer 5777/2017

To cope with the bullying, he would go into his homemade happiness box where he got to practice his happiness skills. He explained to me how this book helped him focus on what was positive in his life so he could cope and eventually thrive. Which work do you consider to be your best? I consider Let’s Stay Safe and Talking About Private Places to be my most important published books. My favorite book is Hashem’s Candy Store because I love Dena Ackerman’s wonderfully whimsical illustrations. Aliza in MitzvahLand teaches children that we are in this world to be givers, not takers. My children learned not to be bored—there are always mitzvot to do. Let’s Appreciate Everyone was written after my granddaughter was born with disabilities. Everyone kept saying, “Now, you’ll write a book about disabilities.” And that’s what ended up happening because my eyes were opened and I became more sensitive to the issues affecting children with disabilities. Recently, I started to write books for the general public, not only the frum community. You touch upon certain sensitive topics in your books. Can you explain what caused you to tackle these topics? Through my work as director of the Jewish Big Brother Big Sister Program (JBBBS) of Jewish Community Services in Baltimore, I have become aware of sexual abuse and how it affects children. Sexual abuse also affected my own family. I didn’t have a book to teach my children about

sexual abuse awareness and prevention when I raised them. I taught my children about stranger danger but I didn’t know that far more often, it is a familiar person who presents this type of danger. I saw a gap that I felt was vitally important to fill. What advice would you give to a child who wants to be a writer? Everyone carries stories within them. I tell people that it takes twenty years and twenty minutes to write a story— twenty years to sit down and write, and twenty minutes to actually write the first draft. Just do it! I have been rejected so many times. The day I receive a rejection, I try to send out a manuscript again right away. That keeps the momentum going. What are you working on now? A number of projects. For a new publishing company, Jewish Children’s Book Club, I am working on a book based on Where’s Waldo? that is about looking for hidden mitzvot, and also a book about the courage of Daniel. I just completed my thirty-third book called Where’s God? The book, which was written for a general audience, is about a boy who searches for God. The book answers the questions that children everywhere ask in a way that fills their souls. It Only Takes a Minute, to be published by HaChai, demonstrates the amazing things we can accomplish in a very short time. We are all here to accomplish unique missions in this world. I have a magnet on my fridge that says, “Here is a test to find out if your mission in life is finished. If you’re alive, it isn’t.”

BEST SERVED WHENe You'r

CHILLED.

Summer 5777/2017 JEWISH ACTION

25

WHAT’S ON YOUR CHILD’S READING LIST THIS SUMMER? Jewish Action asked a number of educators to answer the following: Which book would you recommend children read this summer and why?

Young Children The summer, or frankly any other season, is the perfect time to read or listen to poetry. The Random House Book of Poetry for Children (New York: Random House, 1983) is a wonderful collection of poems for elementary school children. The volume includes classics like “The Crocodile” by Lewis Carroll, “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” by Robert Frost, and contemporary poems reflective of our students’ lives, like “Since Hanna Moved Away” by Judith Viorst and “Homework” by Jane Yolen. Funny poems, silly poems and tonguetwisters by poets like Shel Silverstein, Dr. Seuss and Maurice Sendak complete this volume. Reading poetry is a wonderful way for children to enhance their decoding, comprehension and fluency skills. For reluctant readers, poems often provide a way into the world of children’s literature; their shorter length, rich 26

JEWISH ACTION Summer 5777/2017

language and poetic devices— metaphors, similes, personification and onomatopoeia—help the reader visualize and understand them. Poems can also serve as “mentor texts” and inspire young readers to become poets as well. Risa Zayde, director of curriculum and faculty supervision, Ramaz Lower School, Manhattan Peanut Butter and Jelly for Shabbos (Brooklyn, New York: Hachai Publishing, 1995) by Dina Rosenfeld is just the right type of book for a parent or sibling to read to a young child. Children (and adults) are entertained and intrigued by Yossi and Laibel’s increasingly complicated attempts to solve a problem. The theme is presented in a charming rhyme that reinforces the lesson without becoming pedantic. There’s humor, delightful illustrations and a satisfying ending.

Experience Lander College for Men

What if there were a college where students could experience an immersive Torah atmosphere, receive a rigorous, personalized education and achieve real world success? There is.

Lander College for Men. Beis Medrash L’Talmud. A division of Touro College. For more information visit lcm.touro.edu or contact Rabbi Barry Nathan at 718.820.0400 ext. 5019 • barry.nathan@touro.edu

Summer 5777/2017 JEWISH ACTION

Touro is an equal opportunity institution. For Touro’s complete Non-Discrimination Statement, visit www.touro.edu

27